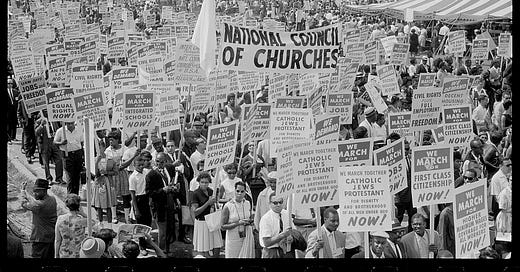

Photo: March on Washington, 1963 (Library of Congress)

Recently, I have written articles about what Christianity and Judaism have to say about housing as a human right. Those articles are set to be released in religious publications soon, and similar articles on Islam and other traditions are in the pipeline.

This is a recurring theme for me. I’ve written a lot on multifaith advocacy for human rights, including the U.S. access to healthcare movement and even a book about the rich legacy and current movement of religious folks committed to socialism.

Many people are alienated from religious traditions, often for very understandable reasons. And active engagement in religious communities has dropped significantly in recent years. So it is fair to ask why I and others believe religious communities have an impactful role to play in housing advocacy. Here are four answers to that question:

1. Religious communities are already engaged in the housing struggle.

Religious communities and religion-motivated individuals are already “walking the walk” on housing by directly providing housing for people in need. In my own community of Indianapolis alone, the Episcopal and Roman Catholic dioceses and evangelical churches operate their own homeless shelters and housing programs. So does another organization that relies deeply on an interfaith network of Jewish, Christian, Muslim and Hindi congregations and organizations. At a national level, religious efforts include Catholic Charities USA, whose affiliates provide homeless services to 400,000-plus people a year and operate 37,000-plus affordable housing units.

That kind of direct service and expertise provides a platform for meaningful advocacy. The federal HOUSED campaign led by the National Low-Income Housing Coalition, which features a call for universal housing assistance and strong renter protections, is joined by Catholic Charities USA, the Union for Reform Judaism, and the national leadership of the Episcopal and Methodist churches. My son Jack Quigley’s research has uncovered a trove of official resolutions and statements on housing as a human right that span denominations across virtually all religious traditions.

2. Religious communities have been pushing for justice for generations.

More often than not, history-making human rights movements featured religious communities at their core. We can go down the list: the abolition of slavery movement, the labor movement, the anti-colonial movement, the anti-apartheid movement, etc. The most-studied social movement of all, the U.S. civil rights movement, was deeply rooted in the Black Social Gospel tradition. The ongoing struggle against white supremacy still has strong ties to religious communities, as does the current efforts to ensure healthcare for all.

Perhaps the most iconic human rights demonstration in U.S. history is the 1963 March on Washington, which was organized by A. Philip Randolph, the son of an African Methodist Episcopal minister, and Bayard Rustin, a Quaker, and was mobilized in significant part through a network of churches. Access to good housing was one of the core ten demands issued on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial by speakers who included Holocaust survivor Rabbi Joachim Prinz, president of the American Jewish Congress.

3. Religious communities can build on a deep scriptural foundation to advocate for housing justice.

My forthcoming articles on the human right to housing in the Christian and Jewish traditions cover this point in some detail, so I won’t pre-empt them here. But consider the words of Richard Kearney and James Taylor in the introduction to the anthology they edited, Hosting the Stranger: Between Religions: “Hospitality is a central and inaugural event in the world’s great wisdom traditions . . . (M)ost major wisdom traditions, as this volume hopes to show, share a sacred commitment to hosting the stranger.”

There is abundant evidence to back up that assertion, from the Torah (Abraham’s radical act of hospitality in Genesis 18:1-15 provided the model for the commandment to welcome the stranger that is repeated a whopping 36 times in the Torah), to the New Testament (Jesus, born homeless and spending most of the Gospels in that state, made it clear in Matthew 25:38 that he embodied all others who are left without a roof over their head: “I was a stranger, and you invited me in”), to the Quran (“Hast though seen the one who denied religion? That is the one who drives away the orphan, and does not urge feeding the indigent.”). More modern calls to translate these mandates into collective action, not just individual charity, come from every tradition.

4. Religious communities still have a powerful impact on public policy.

Yes, there are now fewer Americans spending their weekend hours in a house of worship compared to past generations. But the impact of religious traditions is still deeply felt, with three in four Americans saying they identify with a specific religious tradition. Another poll shows seven in 10 Americans attesting to religion as being important to them. Religious traditions still matter in policy choices, both in direct impact and in less quantifiable cultural influence.

So I will let the last word here come from Rabbi Aaron Spiegel, who directs the Greater Indianapolis Multifaith Alliance, which has chosen to prioritize housing advocacy, including supporting a multi-congregation eviction court-watching program. “All religious traditions teach that we must take care of the “least among us” and as such, housing is a human right,” Rabbi Spiegel says. “Religious communities have historically functioned as support networks to people in crisis. They are learning that they need to be proactive and part of the solution by preempting housing insecurity.”

This newsletter will make it a point to lift up the already-vibrant religious activism for housing justice—and hopefully its significant growth as we all work to make housing a fully realized human right for all.

I’ve recently become aware of housing opportunities that are the result of the decline of religious communities for women. Large Motherhouses and other residential facilities are mostly vacant, causing the leaders to figure out how to repurpose the buildings for the greater good.

I’m wondering if this movement is being coordinated in any way?